tara | ancient seat of the high kings of ireland

- Ali Isaac

- Sep 18, 2014

- 4 min read

Updated: Jul 5, 2020

The Hill of Tara, also known as Teamhair na Ri in Irish, is located on the River Boyne near Navan in County Meath.

Along with Newgrange, Tara is probably one of the most famous and most visited ancient sites in Ireland, and for good reason; it is believed to have once been a sacred site associated with ancient kingship rituals. Now, there is not much left to see but for the raised mounds, banks and ditches which stretch over this vast and historic site.

The summit is crowned with the Fort of Kings, or Royal Enclosure (Rath na Rí in Irish). It measures 318m by 264m, and is surrounded by a ditch and bank. The most prominent earthworks on the site are the two linked enclosures within it known as Cormac’s House (Teach Chormaic), and the Forradh, or Royal Seat. You can just make out the standing stone, the Lia Fail, in the centre of the Forradh (the left hand enclosure).

Originally, the Lia Fail would have stood before the Mound of Hostages, however, it was moved to its current site in 1798 to commemorate the 400 rebels who died in the Battle of Tara during the Irish Revolution. This standing stone is said to have roared out in confirmation of the appointment of each High King (Ard Rí in Irish), and was brought into Ireland by the Tuatha de Danann, a mythical race of semi-divine people with God-like powers.

The Danann defeated the Fir Bolg at the First Battle of Moytura, and chose to rule Ireland from Tara. A few years later, however, they came under threat from Bres of the Fomori.

At that time, Lugh, who had been fostered to Queen Tailltiu but was in fact a Danann prince, arrived at Tara to offer his services to Danann King Nuada, but the guard on the gate refused to let him and his brave young entourage in, suspecting trouble. Having finally convinced the guard that the Danann were much in need of his various skills, Lugh gained entrance.

He then had to prove his mettle to Nuada, which he did through feats of strength (he threw a stone weighing as much as eighty oxen), strategy (he outwitted Nuada at the game of Fidchel, something similar to chess) and skill (he had to play the harp). At this point, Nuada realised that there was something special about this young man, and it was only then that Lugh revealed his identity.

Nuada convinced his officials that Lugh was the man to lead the battle against Bres and the Fomori… which he duly did, and won.

In the images above, you can see the small Neolithic passage tomb of Dumha na nGial, or the Mound of Hostages, which was constructed around 3,400 BC. It is one of only two monuments on the site to have been excavated, and is said to line up with the sun on the cross quarter days of Imbolc and Samhain.

Although many of the structures which once stood proud here have been wiped away by the passage of time, their roots still remain buried beneath the surface, detectable only by modern archaeological technology. Many of these buildings are said to have been built by Cormac mac Airt, who was High King in the C3rd, Cormac’s House being named after him, and another monument named after Grainne, his daughter who married Fionn mac Cumhall and eloped with Diarmuid.

My favourite story of Tara concerns how Cormac mac Art won his right to be Ard Rí. Cormac’s father, High King Art mac Cuinn, was killed and usurped by his nephew Lugaid before Cormac was born. Cormac was raised by foster parents, but at the age of thirty decided to challenge Lugaid and stake his claim to the throne.

When he arrived at Tara, he came across a man consoling a weeping woman. The man told him that the High King had confiscated her sheep because they had strayed into the Queen’s garden and eaten her herbs. Apparently, Cormac claimed “More fitting would be one shearing for the other,” meaning the sheep’s fleeces should be forfeit in payment for the ruined crops, as both the plants and the wool would grow again.

There are various different versions of what happened next; some say that Lugaid abdicated the throne, declaring Cormac to be wiser than himself; some say he was driven out by Cormac in battle, and still others say he was warned by his druids if he did not leave Tara within six months he would die.

According to Irish mythology, Fionn mac Cumhall came to Tara one Samhain when he was not much more than a boy, to pledge his allegiance to King Cormac. There, he defeated Allan of the Sidhe, who laid waste to Tara every year with fire, and so won his place as leader of the Fianna.

Of course no ancient pagan site worth its salt escapes the notice of the big man himself; St Patrick came to Tara some time after he arrived in Ireland in 432AD.

High King Laoghaire was presiding over the Beltaine celebrations at Tara; all of Ireland was in blackness, eagerly awaiting the King’s lighting of the need-fire, bringing light and heat and the blessing of Eriu to the people and the land. In an inflammatory move (pardon the pun!), Patrick challenged the King by lighting a fire of his own on the nearby Hill of Slane.

The Druids warned Laoghaire that the fire must be put out or it would burn forever, and that’s exactly what did happen; no-one was able to extinguish Patrick’s fire, and the King was forced to admit that the holy man’s power was greater than his own. Patrick was therefore granted permission to continue his quest to convert the Irish.

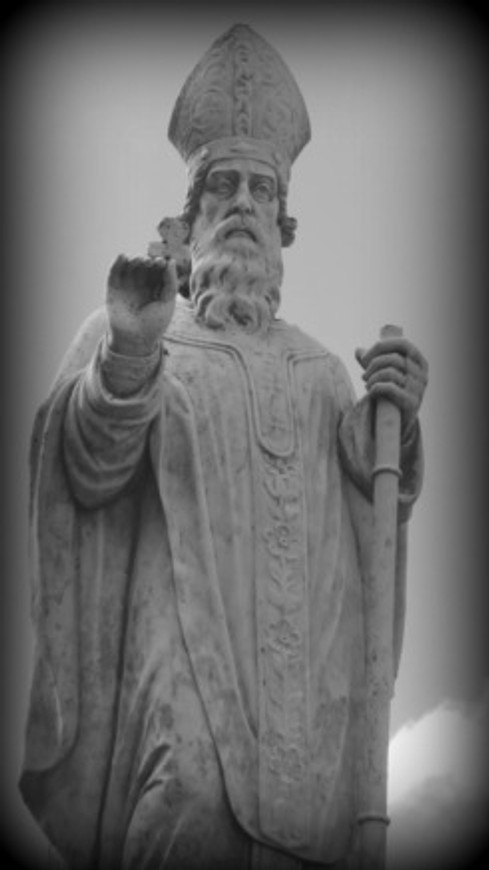

Inevitably, a church named after St Patrick stands on the hill, now converted into Visitor Centre, and Tara is entered through the churchyard, passing an impressive statue of the saint.

Although St Patrick’s legacy and fire still burns strong all over Ireland, Tara will always be celebrated first and foremost as the site of ancient Kings, pagan or otherwise.

Comments